Published:

October 14, 2023

Categories:

Events

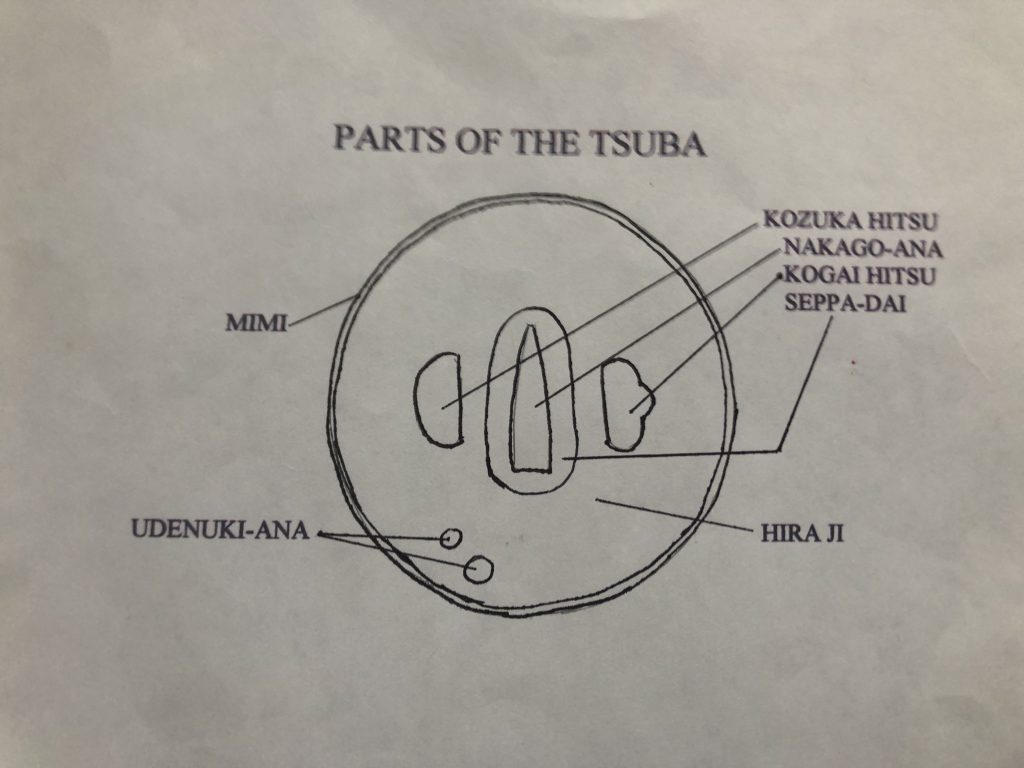

Whilst most people can identify a Japanese sword, many will be less familiar with it’s handguard or Tsuba. This disc helped to protect the Samurai’s hand from his opponent sword cutting down the blade and into the hands.

The mountings of a Japanese sword have changed little over the centuries, it consists of a scabbard (SAYA), guard (Tsuba) and the hilt (TSUKA). The fittings could all match each other, as in a dragon design, fish, landscape, warriors or Family crests (MON) or be built up individually by the owner, a samurai did not wear jewellery, but could exhibit his wealth, status or taste upon his most prized possessions, his swords.

The earliest tsubas were thin plates of iron or leather, lacquered to give strength and protection against the elements. When a swordsmith produced a blade for his customer he also made an iron tsuba to finish it off, later the armour makers began to produce iron plate guards with simple cut out motifs. The dawn of the 15th Century saw more elaborate designs and other metals being used, iron was still a favourite, not just due to its durability in combat, but its simplicity was much appreciated in Japanese culture. Tsuba makers in their own right began to set up workshops and as all things Japanese, schools started to develop either by the town, district or family and hence traditions and secrets began to be passed down from master to pupil.

Copper, brass, gold and silver began to be used, designs using hammering, etching, casting and combinations of hard and soft metals, each school having its own way and methods. The tsuba is a remarkable work of art in itself, so much workmanship is placed on a metal disc about three inches in diameter, some are crammed solid with scenes depicting famous battles or Chinese legends, whilst others have simple, minimalistic work, which the Japanese enjoy so much.

A number of alloys and techniques peculiar to the Japanese were used on sword fittings. SHAKUDO, which was copper, bronze and gold, pickled in a chemical solution, this causes a blackish brown finish. SHIBUICHI, was an alloy of copper, silver, lead, zinc and tin, which forms a silver grey patina.

NANAKO was a series of raised dots on the metal surface, made using a small punch, some are so fine and evenly spaced that they are difficult to pick out even under a magnifying glass, others have even smaller punch marks on top of larger ones.

The tsuba was foremost a protector of the hand, as well as giving the sword balance, the decoration was until the seventeenth century a secondary consideration, as up until that period, Japan had been ravaged by many civil wars, which laid waste cities, towns and villages. In 1601, after much bloody conflict, the TOKUGAWA clan swept to power and heralded the dawn of a new era of peace for Japan which lasted until 1868, when the samurai could no longer wear swords and a way of life came to an end. With the wearing of swords now illegal and Japan becoming westernized, the tsuba artists went out of business, turning their skills to making small metal items such as boxes and cigarette cases for the overseas markets.

It was around these times that the first western collections of sword fittings began to be built up, those on the Grand Tours brought back swords, armour and fittings, which the now poor samurai were glad to turn into cash. Little thought was taken in these early purchases, but many became the backbone of the collections seen in our museums today.